National News

Canada's status as a country without endemic measles can now be revoked

Published 10:50 PDT, Mon October 27, 2025

Last Updated: 12:18 PDT, Mon October 27, 2025

—

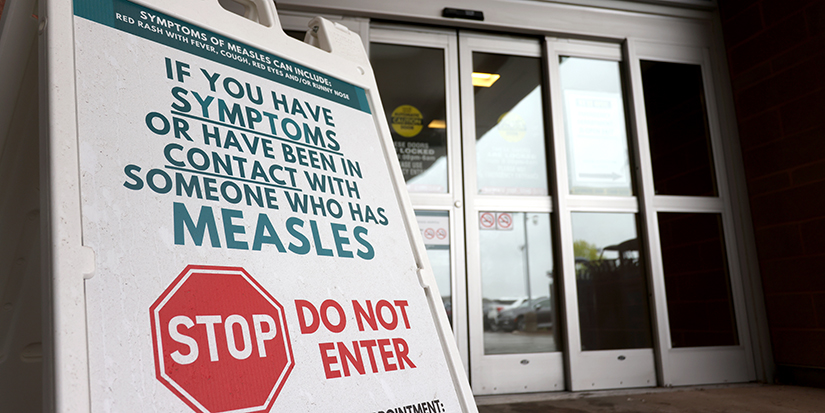

Canada is poised to lose its international status as a measles-free country now that an outbreak that began in New Brunswick and spread to other provinces has hit the one-year mark.

The country eliminated measles in 1998 and maintained that status for more than 25 years, meaning there was no ongoing community transmission and new cases were travel-related.

But since Oct. 27, 2024, the virus has spread to more than 5,000 people in Canada, including two infants in Ontario and Alberta who were infected with measles in the womb and died after they were born.

Public health and infectious disease experts attribute the return of measles to declining vaccination rates, stemming from misinformation-fuelled vaccine hesitancy and distrust of science, as well as the disruption of routine immunizations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Pan-American Health Organization, or PAHO, which is the World Health Organization's regional office for countries in North and South America, will review Canada's measles elimination status at a meeting in November.

Other countries around the world, including the United States, are also seeing a resurgence in measles cases. PAHO said the U.S. outbreak didn't start until January of this year, so it still has some time before it's at risk of losing the elimination status it achieved in 2000.

Dr. Natasha Crowcroft, vice-president of infectious diseases and vaccination programs at the Public Health Agency of Canada, said the unfortunate milestone signals that "we haven't managed to get ahead of the virus," but also marks the importance of doing the work to regain elimination status.

"You have to demonstrate that the country has no ongoing transmission for a period of at least 12 months and you also have to show that all your systems are working well enough to be able to sustain that afterwards," said Crowcroft in an interview last summer when it appeared likely the Oct. 27 deadline couldn't be met.

Those systems include high-quality surveillance to detect suspected measles cases quickly and contain spread, as well as maintaining 95 per cent vaccination coverage — a level necessary to achieve herd immunity against one of the most contagious diseases in the world.

Two other PAHO countries — Venezuela and Brazil — lost their measles elimination status in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Through sustained public health efforts, they both got it back after about five years, a spokesperson for PAHO said in an email.

Crowcroft, who spent several years as the WHO's senior technical adviser on measles and rubella, said until recently, the success of vaccination in eliminating the disease meant only older generations had seen its effects first-hand in Canada.

"They knew the kid who was deaf because they got measles or the kid was behind at school who had a bad case of measles, or ... just how horrible it could be. That's something we've forgotten," she said.

Nicole Basta, an associate professor of epidemiology at McGill University, agreed, saying the current situation should be "a wake-up call for all of us."

"Because we have enjoyed this period of measles elimination for so many decades, I think that the real present threat of measles hasn't been very recently recognized," she said.

"It's another reminder as to how much work we have to do on a daily basis to try to increase vaccination, ensure people have trust in vaccines, that their questions are being answered, and that they have a lot of confidence in getting vaccinated to protect themselves and their loved ones."

Basta, who is the Canada Research Chair in infectious disease prevention, emphasized the importance of building trust and relationships with leaders in communities that are undervaccinated.

"It's really those vaccine champions from communities that help improve vaccination, spread awareness about the need for vaccination, and kind of create the positive change that we need in order to ensure that these outbreaks don't persist and don't continue to happen."

Dr. Cora Constantinescu, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and head of a vaccine hesitancy clinic in Calgary, said now is the time to bring vaccination back to "the forefront of the news and the public and governments" after people grew tired of talking about vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some health-care workers also had some "vaccine fatigue," she said, but the continuing measles outbreak in Alberta has "reignited their fire for advocating for vaccines for their patients and keeping them safe," she said.

The rise of measles in Canada also raises her concerns about possibly declining vaccination rates for other diseases such as polio and whooping cough.

"I did not think that we were going to have such a massive measles outbreak in my lifetime, if you'd asked me that 10 years ago," Constantinescu said.

"Now I'm looking at all these vaccine-preventable diseases and thinking, 'Oh my gosh, they're probably coming and we need to be prepared.'"

———

– Nicole Ireland, The Canadian Press

Canadian Press health coverage receives support through a partnership with the Canadian Medical Association. CP is solely responsible for this content.