International

What to know about Rio's deadliest police raid that exposed limits of anti-gang tactics in Brazil

Published 12:37 PDT, Fri October 31, 2025

—

RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — On Tuesday, police in Rio de Janeiro launched an operation in two of the city’s favelas that left 121 dead, including four police officers, and an unknown number of people wounded.

Brazil’s public defender’s reported 132 deaths in the raid, more than the official police numbers. Police and soldiers launched the raid supported by helicopters, armored vehicles and ground troops, targeting the Comando Vermelho, or Red Command, gang.

Here are some things to know about criminal activity and the large-scale police raids as a strategy to fight gangs:

The origin and rise of Comando Vermelho

The Comando Vermelho, known as Red Command, originated in the late 1970s inside a Rio de Janeiro prison, where common criminals and political prisoners from Brazil’s military dictatorship were held together. They began organizing to protect themselves from state violence behind bars.

Eventually, the group expanded beyond prison walls, establishing itself in Rio’s favelas and entering the drug trade. As Brazil intensified its “war on drugs,” the narcotics market became more profitable, boosting the group’s power, according to Claudio Ferraz, a retired Rio police officer with decades of experience fighting organized crime.

Over time, Comando Vermelho strengthened its territorial control and expanded its criminal operations.

In recent years, the group has grown internationally, especially in Europe. It now competes with its main rival, Sao Paulo’s First Capital Command, known as PCC, for control over international drug routes and territories, according to experts and authorities.

The favelas as a target

This week, the atmosphere was somber in Penha and Complexo do Alemao communities, where the latest raids took place. People's faces were mostly grave, shops shuttered.

Rene Silva, a journalist and activist in Complexo do Alemao said that these operations take a heavy psychological toll. “We’ve never witnessed anything like this in Brazil’s history.”

And after the raids, he said, “Crime continues, everything stays the same."

William de Oliveira, a community leader in Rocinha favela, said it has been a difficult time for residents in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, where he said live all kind of people, not only criminals.

“People in conflict with the law exist everywhere. In the favela, some are involved in drug trafficking or robberies. But there are also those in high society, in any profession. How often do you see police operations and arrests happening in other places?” he asked.

Ineffective, political gains

In August, Brazil launched a crackdown on organized crime, seizing 1.2 billion reais (about $220 million) in assets tied to a money laundering scheme involving the fuel sector and investment funds. Police arrested five suspects and executed hundreds of warrants nationwide, including in affluent business districts, without firing a single shot.

“This operation revealed the connection between crime and wealth,” said Daniel Hirata, a sociologist at Fluminense Federal University who maps criminal activity in Rio. “We often associate organized crime with urban poverty, but it survives through ties to political and economic elites.”

The university’s Study Group on New Illegalisms has recorded over 1,800 police operations in Rio’s metropolitan area this year. Only 1.3% were deemed effective, based on arrests and casualty counts.

In 2024, police killed 6,243 people in Brazil — 14 per cent of all homicides — according to the Brazilian Forum on Public Security.

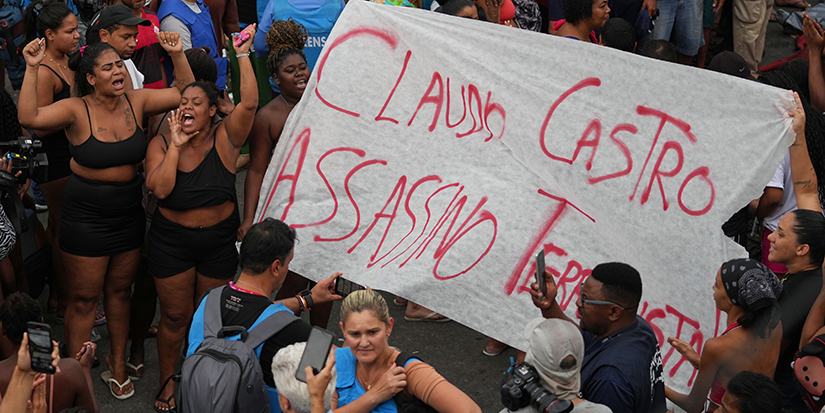

Rio de Janeiro Gov. Cláudio Castro called the recent operation a “success,” despite the deaths of four officers. But with hundreds killed, retired police officer Ferraz described it as “barbaric,” viewing the raid as part of a political struggle for control of the city.

As Brazil prepares for presidential and local elections next year, polls show violence is the top concern for most Brazilians. For some, high-profile raids may serve as a strategy to gain votes, Ferraz said.

A political battleground

Castro, an ally of former President Jair Bolsonaro, has described local criminal groups as “narco-terrorists” in official statements about recent police raids, echoing the Trump administration in its campaign against drug smuggling in Latin America.

Conservative lawmakers have also been pushing for changes in federal law to define drug gangs as terrorists. Sen. Flávio Bolsonaro, one of the former president’s sons, said on social platform X he was “jealous” of U.S. military operations targeting smuggling boats in the Caribbean.

Earlier this year, Rio’s state security secretary, Victor Santos, said he planned to send intelligence reports from the state’s police forces to U.S. authorities seeking formal recognition of Rio’s criminal groups as “narcoterrorist organizations.”

But security experts and the administration of leftist President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva reject that terminology.

Brazil's Justice Minister Ricardo Lewandowski told reporters Wednesday that Brazil’s drug gangs do not meet the legal definition of terrorism under national law because they don’t engage in violence for political or ideological means.

Calls to investigate the latest raid

Human rights organizations have called for investigations into the deaths, describing the operation as one of the most violent in Brazil’s recent history.

The police operation ignited a national political debate. Gov. Castro blamed the federal government for not offering support, while Minister Lewandowski said no request had been made and pushed for a bill to unify police intelligence systems across Brazil.

In response, the federal government sent representatives to Rio and announced an emergency office to combat organized crime. President Lula also signed a new law strengthening efforts against criminal groups, and the Senate will launch an inquiry next week into expansion of organized crime.

———

Gabriela Sá Pessoa reported from Sao Paulo.

– Gabriela Sá Pessoa and Eléonore Hughes, The Associated Press