Latest News

Some gut bugs keep us healthy: new research

Published 10:39 PDT, Thu October 4, 2018

Last Updated: 2:12 PDT, Wed May 12, 2021

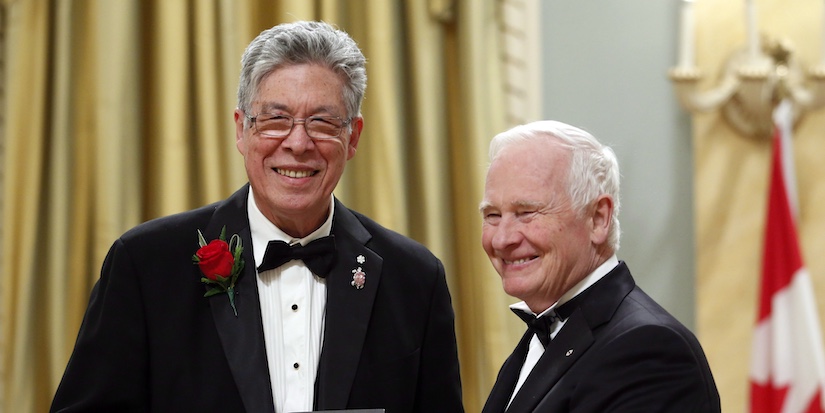

Richmond’s Brett Finlay could have gone

anywhere after he first got his PhD at the University of Alberta and then had a

post-doc position at the prestigious Stanford University south of San Francisco

under his belt.

“I was offered jobs at Harvard and MIT but

I'm a Canadian. I wanted to come back to Canada.”

At the time, Nobel Prize recipient Dr.

Michael Smith was starting his biotech lab at the University of British

Columbia.

“He was instrumental in recruiting me here to

do good science in Canada. He was my boss for at least a dozen years. He’s the

reason I’m here.”

Today, Finlay’s position is the Peter Wall

Distinguished Professor in the Michael Smith Laboratories at UBC. He

acknowledges his job title is a mouthful. It gets longer: Finlay is also

co-director and senior fellow for the Canadian Institute for Advance Research’s

Humans and Microbes Program.

“Historically I made my career my microbial

disease like E. coli 0157 and salmonella, diarrhea causing microbes. About 10

years ago, we were as a lab wondering about all those other microbes in and on

us, do they do anything.”

Finlay tells the story of how his career with

gut bacteria morphed: “So then we started to look at if they could have an

effect in diarrheal diseases.”

Diarrhea is more than a nuisance. It is a

killer. Around the world, it kills half a million children every year. Diarrhea

kills more people every year than malaria or HIV. Finding a way to make people

more resistant to it, could save many lives.

Instead of studying humans directly, Finlay

started small, with mice: “We looked at mouse strains that were resistant and

those who would die of the disease. Then, we did fecal transfers.”

Finlay found that when the poop from the

healthy mice, who could stave off diarrhea, went into a kind of mice who got

the scoots very easily, the sick mice got better. If they did a poop transplant

from the mice who usually got diarrhea into the mice who didn’t, the healthy

mice became ones who got diarrhea easily.”

Finlay discovered that by changing the gut

bacteria, you could change how healthy they were.

“It was a remarkable finding. That opened the

Pandora’s box for us, or black hole,” he says with a smile.

While poop transplants have moved into the

human realm, Finlay cautions they don’t cure everything.

“That got us into the world of (gut

bacteria). We all knew the bugs were there, but didn’t know what they do in

terms of life in general,” Finlay says.

Then the work took another turn. Finlay and

his coworkers started to look at how these gut bacteria might actually

influence the immune system. The immune system is there to weed out bad bugs

but when it goes into overdrive, people can have things like allergies and

asthma.

In what Finlay calls a major finding, they

discovered that people who had four specific bacteria in their digestive tract

had a low risk of developing asthma.

“And if you’re lacking (these bugs), you have

a very high risk of developing asthma,” he says.

Before his lab’s discovery, scientists knew

the statistics but didn’t know why.

“We knew the risks for asthma,” Finlay says.

Today, 20 per cent of Canadian children have asthma. That’s a percentage that

comes up a lot.

Before Finlay’s group’s research, scientists

knew if a baby were born by C-section it had a 20 per cent greater chance of

developing asthma.

If a baby is breast fed, its chance of asthma

is 20 per cent less than bottle-fed babies. A pet in the house drops asthma

risk by 20 per cent and living on a farm drops your asthma risk by 20 per cent.

Bottom line: breast feeding, pets, farms all meant you were less likely to have

asthma while not being born vaginally meant you were more likely to develop

asthma. Why?

Finlay, through his research, found the

common thread to all those statistics was these four gut bacteria. They don’t

make people sick. In fact, they make people healthier.

Finlay’s views were transformed. Equipped

with the scientific proof that these germs are valuable, he continues his

research and now he’s written a book, “Let Them Eat Dirt: Saving your Child

from an Oversanitized World.”

The book tells parents how dirty to let your

kids get to make them healthier throughout their entire life.

“It’s a book designed for the average person.

You don’t need to be a scientist to understand it,” says Finlay. “It outlines

the rapidly changing new science about how microbes can impact your kids and

what you as a parent should do about it.”

He says of his book, “We detail how the

parent can embrace these microbes. You don’t have to use hand wash 20 times a

day. Soap and water before dinner is a lot. We’ve been getting dirty for a

million years.”

Finlay speaks wistfully about his childhood, “When

I was a kid we were out in the dirt all the time. We built forts all the time.

I grew up in Edmonton and moved to Richmond when I moved to UBC in 1989.”

When asked what he thinks of Richmond, Finlay

says, “It’s great! We’re fortunate we live on the dyke. We get all the dirt we

want out there.”

Finlay says, “We’ve known for 125 years that

germs cause disease. We have been hell bent for the last 125 years to get rid

of microbes. Hygiene works; the amount of infectious diseases in the last 125

years has gone way down.”

But he says, we have gone too far: “I call

this the hygiene hangover. We are getting so clean now that we are depriving

ourselves of the little microbes (that we need to be healthy).”

Noting the number of kids with asthma has

risen since the 1950s, when antibiotics first became widely available,

antibiotics that may damage the good bugs in or on our body, Finlay says, “We

know this lack of microbes pushes you towards asthma. Allergens do play a role.

Allergens are not new. Why this sudden increase?”

Switching from mice to humans, Finlay’s been

busy.

“Genome BC funded a fantastic study looking

at 3,500 children across the country to study the microbes in respect to

allergy and asthma. With that, we were able to study their microbes and the

molecules they make and other factors they make. Now, we are really

spring-boarding off that with a $10 million grant to several of us to really

nail it down,” he says.

“The microbes, they help your immune system

develop normally,” says Finlay. He says that if you don’t get enough of these

bugs in your system, you are at more risk for asthma (because) the immune

system is not being developed properly. It’s changing how we think of the

world.”

There are many questions they hope to answer

with their Genome BC grant such as, “Can we put these microbes back into kids

if they don’t have them?”

Finlay continues Michael Smith’s legacy. Dr.

Smith worked in genetics and genomics, the study of DNA, the stuff of life, the

script that writes the stories of our lives, just as Finlay and his group do

today.

This week there are many celebrations

recognizing the 25th anniversary of Michael Smith’s Nobel Prize for discovering

a technique in chemistry. According to the Michael Smith Foundation for Medical

Research: “This (genetic) technique has become one of the foundations of

biotechnology and has given rise to new diagnostic tests and treatments for

genetic diseases.”

Many also reminisce about a man who was

well-loved by those he met and those who worked with him. One outstanding thing

about Dr. Smith is the number of women researchers he took on board in his lab,

encouraged to excel and who, unlike the norm, stayed in science and soared.

BC’s first Nobel Prize came with

approximately $1 million. Smith used that money not for himself or even his own

research pet projects but to further research into the genetics of mental

health, to support science awareness through Science World, and to encourage

more girls to go into science through the Society for Canadian Women in Science

and Technology. Those endowments continue to this day to further Dr. Smith’s

goals.

When he later won Royal Bank Award for

Canadian Achievement, he gave the companion grant to the BC Cancer Foundation.

Later, the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) was formed. It

is British Columbia's health research funding agency, funded by the province of

BC. In honour of Dr. Smith, MSFHR helps develop, retain and recruit the

talented people whose research improves the health of British Columbians,

addresses health system priorities, creates jobs and adds to the knowledge

economy.

Finlay remembers Dr. Smith: “He was an

incredibly enthusiastic warm, gentle, great person. He loved science. He

absolutely loved science and hearing about new things. He let us have as much

as we could to let us do our thing. His job as director of the biotech lab was

to facilitate us doing what we could do best: science.”

Finlay points out that the lab was renamed in

honour of its founder: “The Michael Smith lab has flourished ever since. I

couldn’t ask for anything more.”