Sports

Coach Jack hangs up his cleats

After four-plus decades coaching the Richmond Kajaks, Moseley Jack has retired

A sunny spring morning dawns on Canada’s West Coast and, as always, Moseley Jack rises from his slumber prepared to greet it with cheer.

But this day will be different from many the ever-energetic Richmondite has enjoyed during his 85 years. It won’t include an obligatory trek to Minoru Park to greet a receptive group of teen track enthusiasts anxious to heed his wisdom. Jack, you see, has hung up his cleats after more than four decades as a popular sprints coach with the Richmond Kajaks.

But it won’t be an easy adjustment, either for himself or the club that adores him.

“It’s really hard to put into worlds the effect that Moseley has had on our club and our community,” says head coach Garrett Collier. “When you think about it, whether you ended your career after elementary school, high school or as a decorated national team member, as a Kajak there’s a good chance you got your start with Coach Jack.”

Collier’s own start (before focusing on becoming an accomplished thrower) was picking up the finer points of running from Jack while learning to appreciate his no nonsense approach to developing athletes.

“He was honest, sometimes brutally, (but) supportive as seen in the relationships he’s maintained with current and former athletes over the years.,” Collier says. “His dedication is seen in the countless hours spent at the track. Above all he aimed to produce resilient athletes. As an athlete and a coach I’ve always had the highest respect for Moseley. Good coaches are dedicated to continual learning in order to better care for their athletes. Even after returning to B.C. (from competing and coaching in Hawaii) I was struck at how he still had that energy to learn new things as a coach.”

The Kajaks Track and Field Club will miss having Jack around the track, but will forever be thankful for having had him as a cornerstone to the 60-year-old club.

Jack was nimble and quick

As a boy in his native Trinidad, Moseley Jack was both nimble and quick. Indeed running—sprinting to be precise—was always something at which he stood out. But sadly with the absence of someone to provide training, there was no opportunity to harness and build on that natural talent.

“We’d run in the neighbourhood or just on the street,” he recalls, noting that his high school years were mainly spent playing soccer and helping his team to a league championship. Clearly a natural athlete, he also showed an aptitude for cricket and table tennis. He also took an interest in weightlifting, following the lead of an older brother who for five consecutive years was Mr. Trinidad as a body builder.

But it was a chance meeting while caddying at a golf course that would set the course of his life.

“Trinidad didn’t have free education after Grade 7, so if your parents couldn’t pay, well that was it,” says Jack. “While I was caddying, I was asked if I could pick up golf balls for this American woman who was learning the game and married to the captain of the Trinidadian team. One day she asked the golf pro, ‘Why is this little boy not in school?’ When she learned my parents were too poor to send me, she offered to pay. In exchange, on weekends and school holidays I had to go to the house where they lived and do little chores and help the servants with whatever needed to be done.”

That opportunity, for which Jack will always be grateful, has given him a lifelong appreciation for learning.

Paying it forward

By chance, a clerk at the department of culture—where Jack landed a job after graduating high school—had friends who were attending school in B.C. Keen on hopefully getting a post-secondary education, he asked them to send a university calendar.

“I knew something about B.C. because of the Empire (now Commonwealth) Games,” he says. “There was a guy, Michael Agostini, who had run for Trinidad.”

Short story, Jack found his way to Vancouver and got a degree in education, while serving a practicum teaching at Florence Nightingale Elementary School in East Vancouver. Armed with a newly-minted teaching certificate, and with the support of a friend, he got a full-time job in Kamloops. He was grateful, but also wanted to give back and signed up to coach track and field and soccer at the school.

Later, he found his way back to the Lower Mainland and to a teaching gig in the Richmond School District. Though he was now settled in Richmond, with a young family, Jack continued to support his kids’ sporting ventures which ultimately led him to volunteer with the Kajaks, forging a 41-year relationship.

“I started coaching my son’s soccer team and then went on to coaching the Kajaks, and I didn’t stop there. I also learned to coach basketball. I was always interested in learning as much as I could, and what I didn’t know I reached out to others to teach me. I’m still learning.”

Value of sports

Watching his children participate in athletics remains one of the highlights of his life. Son Byron, who he coached alongside for many years with the Kajaks (and with three degrees has clearly also inherited his dad’s penchant for learning), showed early a talent for sports as did Jack’s daughter Arietha. For nine years in a row they qualified for the Oregon Relays, making the trip to the prestigious meet in Eugene an annual family ritual. When she was 17 Airetha won the javelin competition at the meet. Byron, in addition to continuing to be a jumps coach for Kajaks, has also gone on to coach athletes at UBC and has guided his Lord Byng Secondary School teams to 10 consecutive district titles.

“When I was coaching I was mainly concerned about encouraging the kids—not discouraging them,” Jack says. “I’d tell them, ‘When I attempt to correct you, it’s not a criticism. I’m trying to encourage you to perform better at whatever you do.’”

Though he has lost a second son and his wife in past years, he is grateful for what he has—and to live in what he calls “paradise.”

“I was just telling Byron the other day how lucky we have been.”

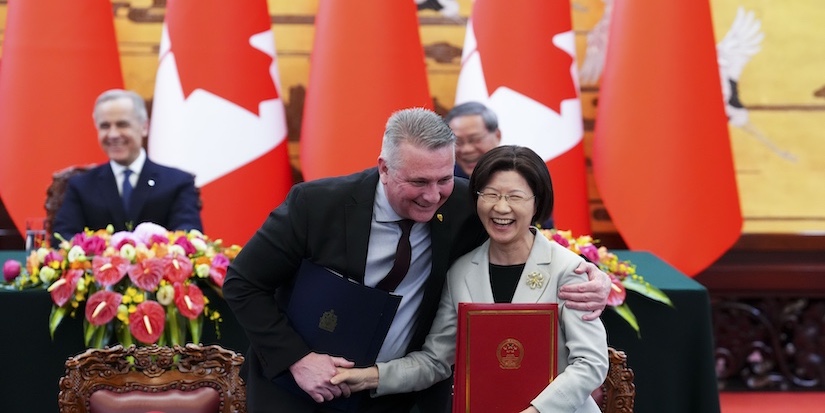

Moseley and his son Byron share a love of track, coaching, and learning. Photo by Don Fennell