Latest News

Coast guard’s Richmond base home to years of history

—

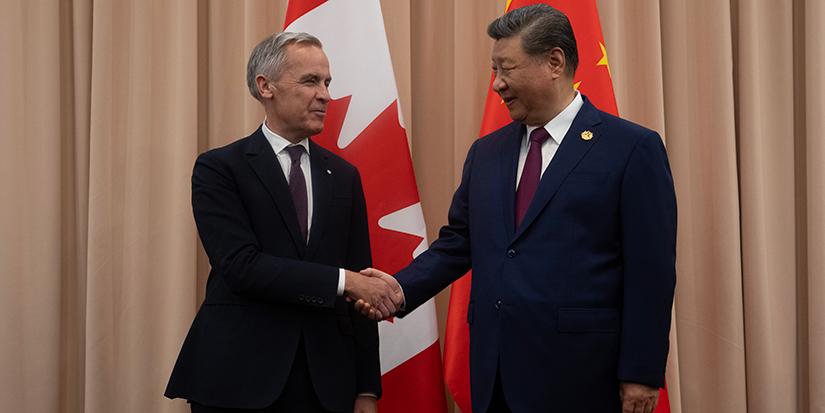

The Canadian Coast Guard is celebrating its 60th anniversary in 2022, and Paul Tobin is the officer in charge of the Sea Island Base in Richmond.

People know about the great work you do with sea and rescue. What really impressed me is the amount of environmental work you do. Right now, you are into the science work season, (correct)?

Our primary role is search and rescue but over the years with global warming, we’ve gotten more involved with scientific research. We’re contracted by the University of British Columbia and National Research Canada. We have special equipment on board, and we take a science team out to monitor the straits for microplastics and heavy metals in the water. Also, we check the mud flats when they’re totally dry around the Sturgeon Banks area.

We’ve been collecting data and monitoring the situation for over 30 years. The Iona Sewage Treatment Plant that’s right at the end of the (Vancouver International Airport) runway is in a constant state of monitoring to ensure the water is healthy for all habitats.

Is it accurate to say that the Fraser River is the mouth to the Pacific Ocean with (environmentally) sensitive lands like across the river, (and) are they constantly monitored as well?

That’s correct. Right now, there is an eelgrass (seagrass) study at Garry Point, where they are looking at the eelgrass and the impact on environmental conditions. A lot of people don’t see that this is happening unless they are out on the water. That’s just one of the tasks that we do. The Fraser River is one of the busiest waterways in Canada outside the St. Lawrence with traffic from commercial fishing, marine traffic, the ferry docks, and cargo ships transporting cars from overseas.

Paul Tobin is the officer in charge of the Canadian Coast Guard’s Sea Island Base in Richmond.

It was just a few years ago when they shut down the Kitsilano (coast guard) base. That was re-opened recently, but they’re more focused on the harbour itself, whereas your territory is a lot bigger—not that there is a competition, but the duties you have are fairly numerous.

For sure, because of the capability of the all-weather machine and speed and our amphibious capability, if we have a rescue happening where a conventional boat can’t get into shallow water or around rocks or reefs, the hovercraft is the only equipment that can be deployed to safely evacuate people off the vessels. We have the only capable dive program on board.

We have five divers so we are a multi-task platform, whereas a conventional vessel will patrol an area like English Bay, Howe Sound, (or) congested areas like False Creek where we don’t want to take the big hovercraft. It’s more efficient and safer to take a small coast guard boat and that’s been operating effectively for a number of years.

Are (you) the only full rescue dive team in Canada?

For the Canadian Coast Guard, yes. The Canadian Coast Guard is a national program that we have defined at Sea Island Base, as a unique operating area because of the amount of boat traffic and risk of roadways close to the water. They studied the data over the years and defined us as having an impact on saving lives, so we’ve been funded for a fully-supportive dive team on board which is pretty unique in Canada.

We also have remote control operator vehicles with cameras and manipulating arms. We’re just doing a search now, up in the Fraser River with the RCMP, for a plane that’s been missing for a couple of years.

The region that you cover is vast—you can cover up to the north part of Vancouver Island and south to the border and beyond if needed?

I’ve taken this hovercraft behind us up as high as Ketchikan (in Alaska) for a joint (United States)/Canadian pollution exercise. We have about a 10-hour duration before we have to stop for fuel, so from here in 10 hours we could be as far north as Campbell River. Last year we took the craft up to Ucluelet (and) Tofino to do some particular navigation work. We left here at 7 o’clock in the morning and got to Ucluelet at noon, so it’s pretty fast.

These (rubber mats that go underneath the hovercraft) are called fingers, the magic part of the hovercraft that the people don’t see. There are 113 fingers underneath the hovercraft and they are like the soles of your shoes. These wear out after about 800 hours annually and we replace all 113 of these, at a big cost savings. We buy the raw stock rubber locally and our on-site, laser 3D-multi-cam machine cuts them out automatically. In the old days we had to cut these out by hand with a razor knife and pound out the holes, so it was really labour-intensive.

By (your crews) doing this here on the base, as opposed to ordering from somewhere overseas, would you be saving a couple hundred thousand dollars?

From England if you buy these, they are $800 each. When we build them, all our costs are about $120 each, so it’s a huge cost savings. These are known costs and we have to do them every 800 hours. By building them ourselves, the first run of 113 fingers basically paid for the machine, so it’s really cost-effective.

I would call this (area) the cockpit, but that’s not what it’s called on a hovercraft.

In the old days, the hovercraft came out of the aircraft industry, but now we call it the control cabin.

Can you explain how you hover right down into the water?

For high speed, we have to overcome some water dynamics; we push the water forward which creates a lot of wake. By the time we hit the bottom of that ramp we’re probably at about 25 knots.

What’s great about this modern-day hovercraft is that it’s very sensitive to the environment, (correct)?

Yes, in the early development of the hovercraft they used them as minesweepers, as there’s no sound in the water that could trigger the mine, so they actually went over the mines and disarmed them that way. That’s one of the beauties of the hovercraft and of course there’s no wake at high speeds. You see the estuaries on that island, that’s a bird sanctuary—they’ve studied these (hovercrafts) over the years and found no significant impact compared to a conventional vessel. We’re pretty environmentally conscious, as part of the coast guard mandate is to protect the environment.

You are surprisingly close to (Vancouver) International Airport. If there was a plane crash, this kind of ship allows you to get into areas that other equipment may not be able to get into.

We’re trained for that. In the containers (outside) you can see it says “YVR life rafts”—they’re all set up for mass casualty events at the airport. That gets deployed on the hovercraft and we can be out at the end of the runway in a matter of minutes.

This is something that you are all proud of: you’ve been here since 1968, (and had the) first female hovercraft pilot, am I right on that?

Yes, and she went on to become one of the BC Ferries captains. One of the first original (officers in charge) on the base in 1968, Captain John McGrath, was influential in the development of technology and diversity of search and rescue personnel in the coast guard itself, because it was predominantly a male-orientated industry back then. He was ahead of his time to have that inclusion factor.

As I said to you at the beginning of the interview: we don’t always see you, but you’re there. The average citizen probably doesn’t realize the number of things that the Canadian Coast Guard does. Continued success and safety for your crew.

Thank you. Our coast guard motto is “Safety First, Service Always.”

For the full video interview, visit richmondsentinel.ca/videos

Jim Gordon is a contributing writer to the Richmond Sentinel.

Paul Tobin (left) shows interviewer Jim Gordon the control cabin of a hovercraft.