Latest News

Gene editing still controversial field

By Hannah Scott, Local Journalism Initiative reporter

Published 12:22 PST, Mon January 27, 2020

Last Updated: 2:13 PDT, Wed May 12, 2021

—

The farmers of Richmond can benefit from gene editing.

Through this process, scientists can choose which genetic material to keep and which to change.

It is a proposed alternative to cross breeding, a simpler process that combines genetic material from parent organisms and randomizes it in the resulting offspring.

Honeygold apples, for example, are a result of cross breeding. Golden Delicious and Haralson apples were grafted together with the intention of creating a product with the best qualities of each.

But the results aren’t always so successful.

Take the Africanized bee, commonly known as the killer bee. Trying to increase honey production, two different honey bees were cross bred but the resulting organism proved to be too aggressive.

But the possible use of gene editing for humans raises some ethical concerns.

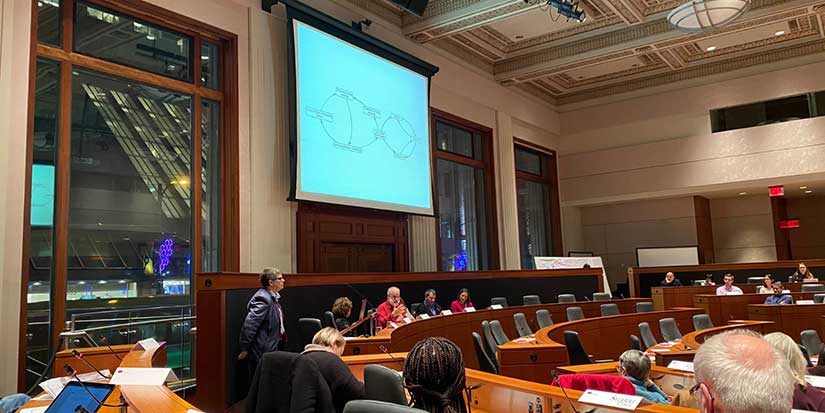

Last week, a Simon Fraser University discussion called “Gene Editing: A silver bullet or a tool for eugenics?” explored the controversial issue.

Panelists questioned whether gene editing is a route to healthier lives or simply eugenics, where breeding is controlled in order to make all humans more desirable.

The panelists developed graphs that visualized the risks and benefits of gene editing.

Dr. Alice Virani, a clinical assistant professor at UBC’s Faculty of Medicine, spoke on the issue of public trust. According to Virani, the acceptance of gene editing is greater when people understand that it can be used to treat debilitating and fatal diseases like muscular dystrophy and cystic fibrosis.

The issue of privacy is apparent in recreational DNA testing—using kits like 23andMe and AncestryDNA—where an individual’s results are made public. This sometimes leads to discoveries of parental or grandparental infidelities, previously unknown family members, or even the surfacing of suspected criminals through DNA.

“Patent is an inherently evil thing,” said Dr. Tania Bubela, dean and professor of SFU’s Faculty of Health Sciences. She says it can be used for good or bad depending on the circumstances.

The patenting of private DNA in order for a company to profit is a long-standing issue. The concern was exposed by the family of Henrietta Lacks, whose cervical cancer cells have been grown and sold without permission for over half a century. Drs. Frederick Banting and Charles Best sold the patent for insulin to the University of Toronto for a token $1, to prevent other scientists from patent it and ensure its affordability.

The panelists explained that the field of gene editing stopped for roughly 20 years after a Pennsylvania teen died as a result of overzealous attempts to use it on humans before adequate testing was done. Now that time has passed, curiosity among scientists has returned although the subject remains controversial.

But Dr. Wyeth Wasserman, vice-president research of BC Children’s Hospital, tells his students to stay alert: “We’re 10 to 15 years away from the tsunami of advances.”

—Lorraine Graves also contributed to this article.