Latest News

Arthritis treatment moving in a new direction

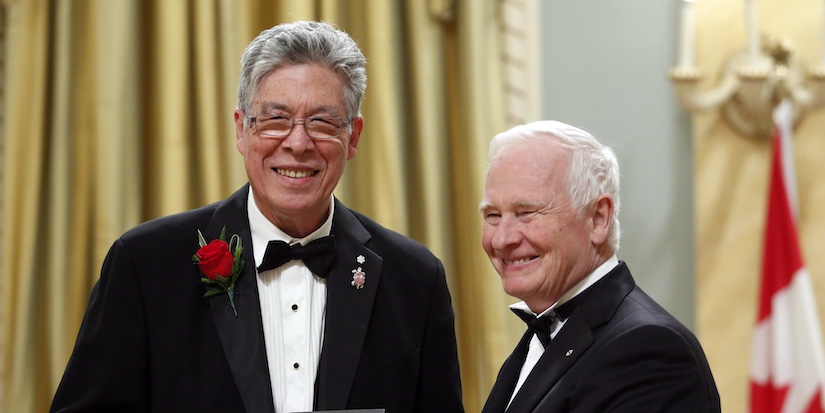

When the Canadian Arthritis Foundation hived off its research arm into a separate entity which became Arthritis Research Canada (ARC) it gained a powerful new ally in the Milan and Maureen Ilich Foundation.

When the

Canadian Arthritis Foundation hived off its research arm into a separate entity

which became Arthritis Research Canada (ARC) it gained a powerful new ally in

the Milan and Maureen Ilich Foundation. The foundation donated two floors in

their Progressive Construction building on No. 3 Road near Lansdowne Centre.

More than

just the floor space, the foundation also donated the cost of operating those

floors. That means all money donated to ARC goes straight to our research and

not to overhead, says spokesperson Kevin Allen.

Described

by scientific director Dr. John Esdaile as one of ARC’s stars, Dr. Linda Li

started her career as a physiotherapist before going onto a PhD and a faculty

position in UBC’s department of physiotherapy.

“I fell

in love with doing research in arthritis and the people I work with in the

field,” says Li. Medical discoveries only become valuable when put to use. That

is why Li aims to make sure that patients and doctors learn about new scientific

knowledge, like the proven value of exercise in arthritis.

“That’s

knowledge translation,” she says.

Li’s

latest research project looks at ways to get creaky joints moving to keep the

cartilage, the cushion in our joints, healthy.

She says

cartilage is like a sponge so, just as you repeatedly squeeze a sponge in clear

water to clean it, the only way to flush nutrients through the cartilage is to

move the joint. The pressure and release when you move a joint flushes the

cartilage with the natural fluids it needs to be healthy.

“Our

study is to look at what it takes to develop the skills and habit to be fit,”

she said.

Li

designed this project because, “Inactivity is the biggest risk to today’s

society for all chronic diseases including arthritis. In fact, not being active

puts you at greater risk for developing osteoarthritis, the most common kind of

arthritis.”

Li’s new

study has three components. The first is educational. Patients learn why they

need to move to keep their arthritis in check.

“We are

trying to instill the concept that moving is good for your joints. We talk

about, ‘Move more. Sit less.’ But we are not prescribing a specific activity or

exercise.”

In the

second part of the project, the participants meet their physiotherapist who

will encourage them throughout the project, helping them set realistic goals,

how to manage pain and how to know the difference between exercise that hurts

their joint and exercise that helps them heal. They will then meet by phone

every two weeks for a couple of months.

The third

component of the study involves an electronic activity tracking device known as

a Fitbit for each participant so they and their physiotherapist can tell if

their gradual fitness plan is working. If a participant doesn’t reach their

goals, they can work with their physiotherapist by phone to see what got in the

way and to set more realistic goals.

“If the

goals weren’t realistic, we can dial them back a bit,” says Li. If the

participant hits all their goals, activity can gradually increase and with it,

joint health.

With the

use-it-or-lose-it philosophy now supported by good science, Li says, “We want

to help people with arthritis, who are not physically active, become more

active.”

Li loves

her research: “I like the complexity of it. The field is full of really good

people, colleagues, and mentors so once you get into it, you don’t want to

leave.”