Latest News

Patient-inclusive research brings new insights

Published 1:52 PST, Wed February 27, 2019

Last Updated: 2:12 PDT, Wed May 12, 2021

Alison Hoens (pronounced Hoons)

lived vibrantly.

“I’m passionate about activity,

as a physiotherapist—both personally and professionally. Movement meant

everything.”

And she lived a healthy life.

“I didn’t smoke. I was totally

active with a great diet. Not the kind of situation that you would think of

first as a risk for an autoimmune disease.”

An autoimmune disease occurs when

a person’s immune system gets it wrong, fighting off healthy cells instead of

bacteria and viruses. Your body attacks itself.

Life threw her an unexpected

curve ball, one she ignored for a while.

“I operated on the principal of

denial for probably about a two-year period and put it down to old war wounds.

As a goalkeeper, I had had a number of significant injuries,” she says.

Eventually her symptoms were

explained.

“I was diagnosed with rheumatoid

arthritis in May of 2012. I knew in the back of my mind, from my training as a

physiotherapist, that I had strong symptoms of it, but I denied them,” she

says.

“Essentially, when I went for

that first appointment, I could barely walk and I just hadn’t perceived it.

When I was given the diagnosis, I thought it was wrong. I didn’t believe it for

about five months even though I was really, really not well,” she says.

To give back for the amazing care

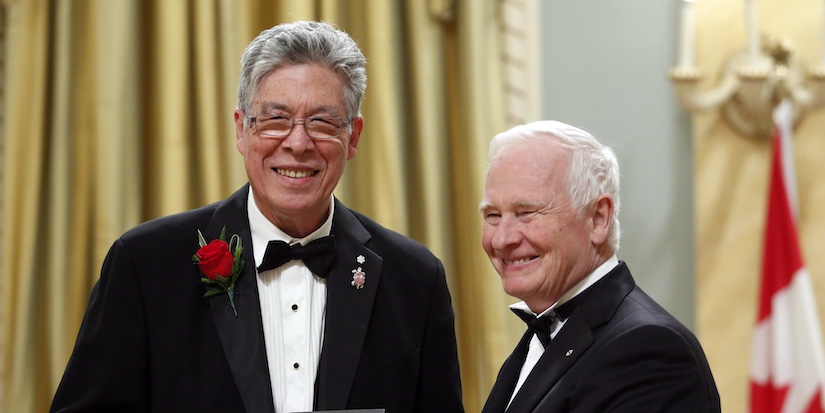

she received, she turned to Richmond-based Arthritis Research Canada.

She spoke with her

rheumatologist, Dr. Antonio Aviña-Zubieta, and he connected her with the ARC’s

Patient Advisory Board (APAB).

One hallmark of arthritis care

has long been patient involvement. Patients understand their diagnosis and

become active partners in their disease management, working with the doctors,

physiotherapists and occupational therapists to adjust their lives in realistic

ways and use treatments that work best for them.

Since 2002, ARC has led the way

in making patients partners in medical research as well—from advising on how

best to deal with their needs, all the way to patients proposing studies.

Originally started by ARC’s scientific director, Dr. John Esdaile, patient

participation in research has seeped into all aspects of arthritis research,

not just a few selected studies.

“It’s just the normal way of

being at ARC so the trainees are raised that way,” says Hoens.

For instance, patient advisors

showed the need for research onbrain fog, the mental mushiness that comes with some inflammatory diseases.

For researcher Jenny Leese,

things didn’t turn out as she thought either. A Brit with a UK degree in the

humanities, she is now a PhD student at the University of British Columbia’s

department of physical therapy and a research trainee at ARC.

“Patient engagement in research

is about carrying on research with patients rather than to patients,” she says.

The paternalistic days of doctors

being the only one to ask the questions and the only one to seek answers are

fading, at least at ARC.

“Patients can be involved from

the very start of a research project even identifying the research projects,

from the very conversation that starts the process around what is important.

From there, they can be involved in preparing the research grant, informing the

data collection process, supporting the researcher to interpret the findings,

and even co-authoring a scientific paper,” Leese says.

She points to a recent studypublished in a respected scientific medical journal: “That paper was co-authored by four patient partners on the project.”

She outlines one example of a

newer avenue of research that doctors hadn’t thought of: “Fatigue is an

excellent example. It opened up a whole new area for research that patients had

identified as being important that researchers perhaps had not fully

appreciated previous to listening to their stories.”

And Leese is an example of what

you can do with a degree in English literature: “I was working with Dr. Anne

Townsend who is a research associate of ARC.”

Leese repurposed her knowledge in

the humanities for her scientific PhD work.

“I was used to analyzing stories

in the canon of English literature, and then I was analyzing stories of people

living with RA, so I had transferable skills.”

Dr. Townsend, also a medical

sociologist in UBC’s Department of Occupational Science Occupational

Therapy, was looking at people’s experiences of living with rheumatoid

arthritis.

“It was a qualitative research

study about looking at how people with it were experiencing their everyday

lives and living with this disease,” Leese says.

“Now that ARC has established the

value and procedures for patient participation, they want to fine tune it,”

says Leese.

So ARC is taking this partnership

one step further, asking their patient advisors what works best for them when

they are participating in a study. Now for her PhD, Leese and ARC ask the

patient partners what works best for them—how best to have them participate and

help guide research while not depleting their scarce spare time or energy.

As Dr. Diane Lacaille’s project

Making It Work has shown, people with arthritis, even severe arthritis, can

continue to participate in life and research but they often have to make

adaptations to allow for such things as fatigue, physical limitations, and

flare-ups—the times their arthritis is particularly painful or debilitating.

Leese says the research issue is:

“How do we do it genuinely? How do we really and truly engage with patients and

avoid it being a tokenistic practice, as well as having it be meaningful? As researchers

how do we make sure that we are actually fulfilling patient participation’s

potential and not just paying it lip service?”

At ARC, they take patients’

advice seriously. APAB has its own board and budget from ARC as well as having

a liaison person on the ARC board of directors. They are integrated in the very

fabric of arthritis research.

Thanks to ARC’s lead “lots of

diseases are learning how to incorporate patient partners,” Hoens says.

And now, almost seven years

later, how is Hoens’ health?

“It’s been a bit rocky. I’ve had

a number of complications. I have had reactions and got a second autoimmune

disorder called autoimmune gastro paresis,” she says.

It’s a condition that slows the

movement of food through the digestive system. Hoens says most people with an

autoimmune disease often have more than one condition to deal with.

It’s not a one-way street. Hoens

says she has the best health possible because of her advisory role: “My being

on APAB and being at ARC had enabled me to be at the front of the wave of

research that has directly helped me.”